Chances are that you know somebody affected by dyslexia; the disorder affects an estimated 5-10 percent of the population, commonly affecting the afflicted with symptoms that make it hard to decipher, interpret, and communicate through written language. Binghamton University Neuroscientist Dr. Sarah Laszlo wants to understand what’s going on in children’s brains when they’re reading. Dr. Laszlo and her team of researchers may untangle some of the mysteries surrounding dyslexia and lead to new methods of treating America’s most common learning disorder.

“The brain can reveal things that aren’t necessarily visible on the surface,” Dr. Laszlo says. “It can tell you things about what’s going wrong that you can’t find out by giving a kid a test or asking him to read out loud.”

Funding from the National Science Foundation is enabling her to conduct a five-year brain activity study of 150 children with and without dyslexia. Rather than lumping all children with dyslexia into one group, as many previous brain-imaging studies have done, Dr. Laszlo’s project will help to establish types and degrees of the disorder.

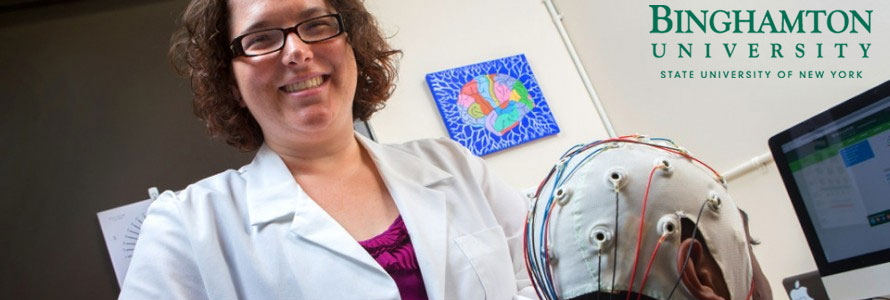

The laboratory uses electroencephalography, or EEG, which is the recording of electrical activity along the scalp. A non-invasive procedure, EEG measures the electrical signals sent between brain cells when they’re communicating with each other. Study participants — kids in kindergarten through fourth grade — wear a cap outfitted with special sensors while playing a computerized reading game.

The laboratory uses electroencephalography, or EEG, which is the recording of electrical activity along the scalp. A non-invasive procedure, EEG measures the electrical signals sent between brain cells when they’re communicating with each other. Study participants — kids in kindergarten through fourth grade — wear a cap outfitted with special sensors while playing a computerized reading game.

These scans produce massive amounts of data: The cap’s 10 sensors collect readings 500 times per second for 45 minutes. That’s one reason that brain activity studies are expensive and time-consuming. It’s also the reason that a study of just 150 children is the largest study of its kind.

Kara Federmeier, a professor of psychology at the University of Illinois, says it’s not just the scale of the study that’s impressive; it’s also the project’s duration. “Sarah will be able to assess how the brain transitions from immature reading processes to mature reading processes,” Federmeier says. “Her project promises to provide important, novel data that may be critical for informing educational practices about teaching reading and clinical practices for assessing reading-related difficulties.”

Why study this disorder in particular?

Dr. Laszlo notes that there are significant, sometimes lifelong consequences of growing up with dyslexia. Many dyslexic children don’t do as well in school as they might otherwise, which limits their career opportunities. Some also encounter social problems. “This has the potential to help a lot of people,” she says.

Dr. Laszlo hopes to identify the brain signatures of people with dyslexia and have a clear idea of how to help them. “Once you understand what’s going on in the brain,” she says, “you can do a better job of designing treatments.”

Today, the best-case scenario is that children with dyslexia receive interventions that enable them to get up to speed on reading aloud. But they may continue to lag behind their peers when it comes to comprehension, fluency and speed. “The treatments we have now don’t always fix the underlying problem,” Laszlo says. “They just put a Band-Aid on it. And when you go to do more complicated things, like reading larger passages, the Band-Aid doesn’t help.”