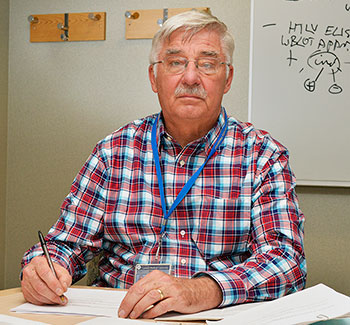

It was 1987. The woman volunteered a sample of her blood to an HIV study led by Bernard Poiesz, professor of medicine at SUNY Upstate Medical University, believing she belonged in the disease-free control group. The studied aimed to test the ability of a relatively new technique—called polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which produces millions of copies of a particular DNA sequence—to detect HIV in patients.

A few days later the woman reported that her husband had learned he was HIV positive. When the study results came in, they did, indeed, include an HIV-positive sample, but the sample didn’t belong to the woman; it belonged to Poiesz, who had also volunteered a blood sample for the control group.

Concerned and a bit suspicious, Poiesz flew to California where the blood samples were being processed. There he determined that the technicians were unknowingly contaminating normal blood samples with HIV in an attempt to cool a heat-sensitive enzyme involved in the process. According to Poiesz, numerous times during the PRC process, the team had to open the sample containers to add more of the heat-sensitive enzyme. In doing so, it appeared that some of the samples were being contaminated.

The scientists at Cetus developed a solution for the problem that eventually led to the use of a heat-tolerant enzyme from a bacterium that lives in deep-sea thermal vents. “That made it doable,” he said. With those changes, PCR remains today the standard method for detecting and quantifying not only HIV, but also another retrovirus, known as human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV), which Poiesz discovered in 1978.

Poiesz was recruited to help develop PCR for HIV and HTLV by scientists at Cetus Corporation. The technology’s inventor Kary Mullis eventually won a Nobel Prize for the work, and Poiesz was instrumental in the technique’s commercialization. For the use of PCR on HIV, the patent was acquired by Cetus Corporation, while the patent for its use on HTLV went to SUNY. At the time, Poiesz’s team received numerous government contracts to apply the technology. “That was an income stream coming into the Research Foundation,” he said. Poiesz also partnered with drug companies to conduct clinical trials. “Back then, there were only a few labs that could do PCR, and we were one of them,” he said.

Today, Poiesz continues his work on retroviruses, especially HTLV-1, which causes HTLV-1 associated myelopathy (HAM), a severe neurological disease similar to multiple sclerosis. “Only a small fraction of the people with the HTLV-1 virus develop HAM,” he said. “We have found that in these people the HTLV-1 virus cross reacts to proteins that are present in human endogenous retroviruses, causing immune reactivity against their own neurological systems.” Poiesz noted that eight percent of human DNA is made up of endogenous retroviruses, or fossils of retroviruses that long ago incorporated themselves into our genomic DNA.

In addition to HAM, Poiesz is investigating a proposed cause of breast cancer: mouse mammary tumor virus. “It’s a very confusing story,” said Poiesz. “Some people have suggested that mouse mammary tumor virus is the cause of human breast cancer in certain cases, but we’ve done a lot of work to see if we can confirm that and we cannot. We’ve studied 100 different breast cancer samples, and we can’t find one of them with clear evidence that there is mouse mammary tumor virus in the sample. Obviously the virus is not the cause of breast cancer in these samples.”

Instead, Poiesz believes contamination may be at play. “Most of the laboratories we interact with have rodent DNA in them from either laboratory mice or wild mice that have gotten in,” he said. “Some of these mice have mouse mammary tumor virus in them. We’ve gone out and sequenced tumor virus from rodents all over the world and we’ve proven that some of the claims are contamination with these rodent samples; however, there are sequences that other labs have found in humans that we can’t match with any of the rodent sequences we’ve examined. So we don’t know how to explain them. Maybe there are rare people who do have mouse mammary tumor virus in their breast cancer. It requires further study.”

A newer area of investigation for Poiesz is a protein found in cell cytoskeletons called tropomyosin. “We discovered new and novel forms of tropomyosin, and in breast cancer we think there are several of these forms that are turned on and several that are turned off,” he said. “When this happens we think they make the cell more likely to metastasize.”

In addition, Poiesz stays busy conducting clinical trials related to prostate cancer. Some of these trials are funded by the National Institutes of Health, while others are supported by pharmaceutical companies. Several of the drugs tested have resulted in FDA approval.

Through all of these different endeavors, one thing has remained constant: Poiesz’s passion for his work. “You’re working to understanding nature and how fascinating it is,” he said. “I think it’s always mesmerizing how complex it is. And I’m an M.D., so I take care of patients; it always feels good to help people. You might not cure a person, but if you can help them and improve the quality of their life then that’s real important.”