The dairy industry is big in New York. From milk to yogurt, cheese, and much more, farmers across the state are providing local goods to homes and restaurants. So if a run of E.coli, staph, or other infections hits a farm, the affects can be compounded and land right on your dinner plate, which nobody wants to experience. That’s where SUNY research steps in to find ways to prevent these occurrences.

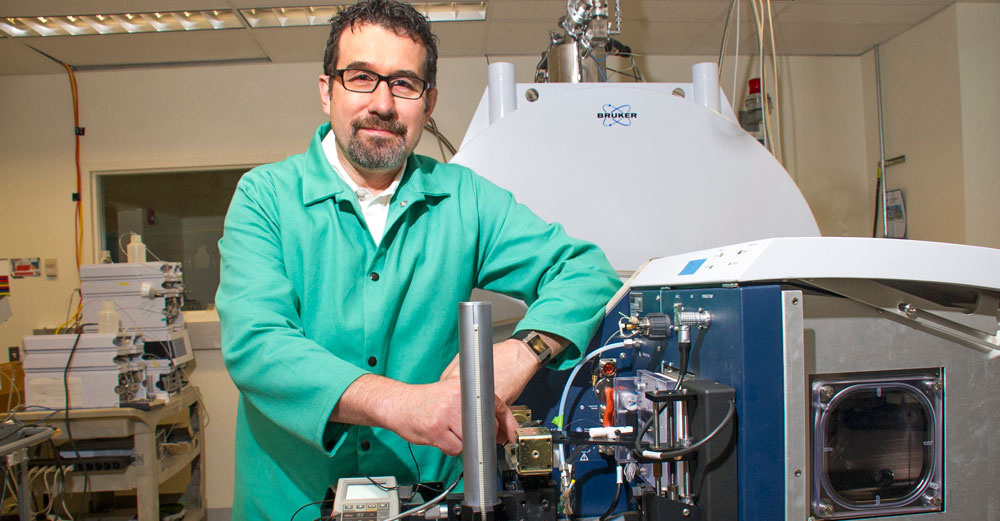

Dr. Daniele Fabris thinks outside lots of different boxes. A senior faculty member at University at Albany RNA Institute and an expert on mass spectrometry, Fabris recently won a SUNY Technology Accelerator Fund (TAF) award for his project “RNA-based technologies for the detection of pathogens in dairy production.” Now in a proof-of-concept phase, the project promises changes in both animal and human diagnostics. It also exemplifies a new focus in basic-science research.

Fabris’s long-term goal is to apply the methodology to human samples to develop rapid, inexpensive diagnostic tests. However, that is a multiyear endeavor subject to the U.S Food and Drug Administration’s rigorous review and approval process.

As such, Fabris began to look for a less-regulated domain where he could advance the proposed methodology more quickly. He found it while participating in the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps (I-Corps) “customer discovery” program. In this intensive seven-week program participating teams conduct interviews with many potential customers and other stakeholders to gain a better understanding of the commercial opportunity offered by their technology.

As part of this customer discovery process, Fabris and his team talked to a range of individuals in the dairy industry — from small and large farmers to dairy owners and Cornell University’s Quality Milk Production Services Laboratory. This led Fabris to zero-in on the dairy industry as a good point of entry. In New York alone, losses due to bovine infections amount to $187 million a year.

If Fabris could use his technology to identify bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus or Mycobacterium bovis — which not only cause mastitis in cows, thereby taking them off the production line, and posing major health problems for humans if they find their way into the milk supply, the commercialization potential could be enormous.

With a viable commercial context for moving his project forward, Fabris set his sights on funding. The TAF program, which helps faculty turn their ideas into market-ready technologies, was a logical choice. TAF investments are awarded through a competitive process, taking into account such factors as availability of intellectual property protection, completion of a customer discovery process, and commercial potential.

A patent application on the technology had already been filed and is currently pending. The I-Corps customer discovery experience had pointed the way to a viable market entry point. And Cornell University’s Quality Milk Production Services Laboratory had agreed to conduct a double-blind study once the project is further down the road.

It was precisely this focused approach that earned Fabris’s TAF application the support of Dr. James Dias, vice president for research, University at Albany; and Theresa Walker, assistant vice president for research and director of UAlbany’s office for innovation development and commercialization. Since the number of TAF applications per SUNY campus is limited, an internal review process was conducted to identify candidates to advance to the SUNY-wide TAF competition.

Says Walker, “Talking to people out there in the real world, Dr. Fabris learned a lot about the industry. It was clear that he had a deep and detailed understanding of how his technology would fit into the world of dairy farmers and dairy safety testing. What’s more, Cornell is a center of excellence in agriculture [Cornell Dairy Center of Excellence], and when their dairy safety lab saw his proposal as a potential step forward, that was another positive in our evaluation.”

Fabris will use the TAF investment to demonstrate, using his high-end $1.5 million mass spectrometer, that his algorithms and methods can not only detect the presence of bacteria in cow’s milk but also discern any changes that result from infection.

Following this proof-of-concept phase, he is hoping to develop a low-cost instrument that can be sold directly to dairy farmers so they can test their cow’s milk on site and get immediate results. Currently, farmers determine whether a cow is sick by observing it firsthand, then taking milk samples and shipping them off to a lab—a time-consuming process rife with possible errors. Even more important, an infected but asymptomatic cow could already have spread the infection through the herd. The ability to routinely test cows, even when they are asymptomatic, can be a game-changer for dairy farmers.

Even before Fabris applies his methodology to medical problems that plague humans, his work in domestic animals in collaboration with Cornell has opened up new possibilities in human diagnostics. Many domestic animal studies, especially at agriculture-centered universities, produce knowledge that is relevant to and may help our understanding of how to treat human disease.

Says Dias, “Cornell has a very, very intentional commitment to agriculture, yet in many cases, studies in domestic animals can reveal basic knowledge that may be implemented in humans. It’s nice to be able to play in both of those spaces while advancing knowledge creation and scholarship that will benefit human health.”

Beyond that, Dias believes that the path Fabris followed in winning the TAF investment indicates a new direction for scientists doing basic research. He explains: “When Dr. Walker and I got our doctoral degrees, we were pretty much married to the idea that we were knowledge creators. Now, when our principal investigators start thinking about possible implications of the work they’re doing, they’re doing it in the context of also understanding how to commercialize that knowledge in order to translate it into working solutions to treat human conditions as well as veterinary needs.”