Alumni Profiles is an ongoing series highlighting successful graduates who, with a SUNY education, achieved interesting and influential careers.

Haagen Klaus is a humanist, professor, and archeologist. Klaus is best known for his work in helping unearth Peruvian human history through his studies as a professor at a U.S. university. Klaus grew up with dreams far from South America—in aerospace. However, a couple decades later, following his own gut feeling and effective mentoring at college by his professors, Klaus is now a research professor in Utah with findings recorded in National Geographic, among other news and scholarly publications.

Haagen Klaus is a humanist, professor, and archeologist. Klaus is best known for his work in helping unearth Peruvian human history through his studies as a professor at a U.S. university. Klaus grew up with dreams far from South America—in aerospace. However, a couple decades later, following his own gut feeling and effective mentoring at college by his professors, Klaus is now a research professor in Utah with findings recorded in National Geographic, among other news and scholarly publications.

1. It seems like your career path was well-established from the very beginning. You were immersed in anthropology studies at Plattsburgh State College and even focused your senior thesis in South America, roughly the same region that your work continues to date. Did you see yourself going as far as a Ph D.? What inspired you to focus on anthropology, especially in South and Central America?

Actually, no. My career path was very much adrift, to be honest, before I experienced archaeology. I grew up in the 1980’s on the east end of Long Island in the shadow of the legendary aviation company Grumman Aerospace. Among other jets, they manufactured the F-14 Tomcat for the U.S. Navy. While other kids my age idolized baseball players and rock stars, my heroes were a group of some of the best experimental test pilots in the world. A few of them even taught me how to fly airplanes when I was a teenager. I had no other desire in life than to follow in their footsteps and become a naval aviator and fly the F-14.

Then, in high school, as I began to examine the process to apply to the U.S. Naval Academy, my perfect eyesight began to degrade. This was back in the era that pilot candidates had to have perfect uncorrected vision. My dream fell apart in an instant. So, I drifted. I drifted for the last two years of high school without a clear vision of my future. I knew I had to go to college, so I applied to Plattsburgh State. It was far from Long Island and I was eligible to participate in the Honors Program which was very interesting to me.

I loved my first two years at Plattsburgh. Dr. David Mowry and the Honors Program provided a true anchor for me. I tried every major under the sun, but nothing really ever “clicked.” So at the end of my sophomore year, I decided to quit school and follow the only vocation I ever had – aviation. The Vermont Air National Guard was nearby, and there were plenty of non-flying jobs available that would still put me in daily contact with launching, recovering, and maintaining jets. It would have been a great and honorable career and a good life. But there was a little voice in the back of my head wondering if this was indeed the right path.

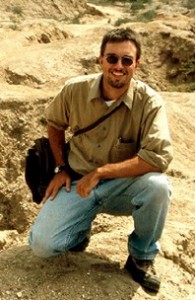

At the same time, an opportunity arose to join Plattsburgh State’s archaeological field school in Clintonville under the direction of Dr. Gordon Pollard. I really loved my past anthropology and archaeology classes I had taken, so I gave this a shot but didn’t expect much. Within the first five minutes on the site, I was beside myself. I had found my path. (Or perhaps, my path had found me.) Archaeology clicked like nothing ever before could have. It combined my love of history, science, exercise of the body and mind, working outdoors, and set my sense of curiosity on fire like an inferno. Only at that point was a career path ever set.

The path to a Ph.D was frankly something that was practical. I would have gotten a doctorate if I wanted a career in this line of work. In order to dig square holes in the ground and conduct your own research independently, a doctorate was a minimal professional requirement. But I must say, this is a great life, and I truly love it.

My focus on South America was initiated when I took a class with Dr. Pollard on South American prehistory. Pollard revealed a profound, unique, and compelling unfolding of civilization in the Andes that was unlike anything in human history. It was captivating and I was driven to know more. At the same time, I felt it was necessary to learn about human remains since they are one of the most commonly encountered materials in any archaeological dig.

Auspiciously, there was a collection of the remains of more than 600 Mayan individuals curated at SUNY Plattsburgh thanks to years work by Dr. Mark N. Cohen. I undertook a series of independent studies involving skeletal anatomy, biology, and pathology for the next two years with Dr. Cohen, and I became equally captivated by what could learned about past human beings and their cultures from their mortal remains. The dead become our teachers. It is frankly incredible, and bones and teeth provide a detailed and intimate portrait of the lives we live.

This converged with my fascination with ancient Peru, and my M.A., Ph.D., and post-doctoral research really were born at that very moment at Plattsburgh State, and I recall like it was yesterday.

2. What is the most interesting study that you have worked on? What is the most surprising discovery that you have helped make?

Trying to choose a ‘favorite study’ is a lot like trying to designate which of your children you love the most. Every time I’ve gone out into the field, I encounter remains that are all important in their ways. Every skeleton is all that remains of a once living, vital human being, and each skeleton has much to tell you. I learn new things during every study I conduct, all contributing to a broader reconstruction of life, history, and society in Lambayeque.

For example, my first time excavating in Peru with Dr. Izumi Shimada’s Sicán Archaeological Project in the summer of 2001, I didn’t find many skeletons, but the burials I did locate opened the door to identifying an entirely new social group or that had been under archaeologists’ noses for nearly a century but the picture had not yet come together. In 2003, I was drawn into work involving the remains of sacrifice victims, and since then, my work on ritual killing has expanded to multiple sites in the valley and more than 300 sets of human remains at this point to reveal the evolution and diversity of ritual violence in this part of ancient Peru over a 500-year period.

Another major focus of my project is the long-term and regional study of contact and colonialism: what actually happened to the culture, biology, and genetics of the local Andean population when the Europeans arrived. Since 2004, I’ve so far conducted large-scale excavations of three abandoned colonial towns, their churches, and their cemeteries. The picture that is emerging challenges in many ways the stereotypes we consider about the European-native contact. We have strong scientific evidence in some locations of successful native biological and cultural adaptation to a disastrous series of events and an oppressive and violent colonial rule that followed. This was quite unexpected.

Another surprising discovery is one I am working on right now. In October 2011, my colleagues and I began to excavate a massive 900 year-old deposit at the city of Sicán. It has turned out to be a gargantuan offering pit probably about half a football field long. So far, we have found the bones of more than 200 individuals—mostly adult men. These men appeared to have been sacrificed in the final days of the Middle Sicán culture during a period of rainfall, which preceded a revolt that toppled the theocratic leadership. The scale, organization, and patterns of trauma are completely unprecedented. This is exciting because, quite frankly, I am still not sure what happened and why. It is a mystery, and we’re still digging.

3. Anthropology is, in its most definitional sense, the study of humankind. You have seen a lot of non-living humans and past cultures in your work. How and in what fashion does this change your value/outlook of your own life and society?

A proper response to this question is probably a book-length answer because anthropology has fundamentally changed just about everything regarding my outlook on reality. As an archaeologist, you deal a lot with the passage of long periods of time. Working with human remains is very humanizing, if you will, as there is but only time that separates your common humanity. It emphasizes your own mortality and the inevitability of your own impermanence and insignificance in the grand scheme of things is something you just have to accept and be comfortable with. Also, with the information bioarchaeology can glean from human skeletons, we really do become a voice for people in the past. We can tell their stories and their histories which would forever be silent and truly lost.

For all its study of buried history, I actually think that archaeology’s greatest potential is this discipline’s ability to tell us about our potential futures. Archaeologists have assembled a scientific history of the last 12,000 years of human history and behavior. You see the cycles of time and the rise and fall of civilizations. You can recognize their triumphs, identify their mistakes, and study their collapse and passage into time. You can identify causes of conflict and violence just as conditions of peace and progress. You can see the consequences of the poor management of resources or gross inequalities of social and economic power — and it never ends well.

Also, there’s a recognition that over the last 200 years, humanity has been doing something totally unprecedented with the simultaneous emergence of industrialism, integrative global economics, biotechnologies, the harnessing of the atom, and our current leaps in computing and communication. The astronomer Carl Sagan recognized this too, and said that at this moment in time, we are at a critical branch point in human history. As an archaeologist, I would say that to make the best choices for the betterment and progress of all humankind, we must consult the past. Visions of our potential future are there.

4. What is the biggest, possibly most difficult question you want to answer through the course of your work as an anthropologist?

Running a long-term field project in a foreign country sometimes is more challenging and than I care to think about. After getting permits and other elaborate administrative tasks, organizing a dizzying range of logistics, assembling a multinational team, renting a house, and providing food and medical care, digging turns out to be the easy part by comparison! Much of this is behind-the-scenes, so students and other project members never need to worry about such factors. People count on you for pretty much everything, and you are responsible for the lives, safety, and well-being of your students and team members. It’s never easy, but it does get more predictable the more you do it. And of course, the end result is worth it.

Topically, I am deeply interested in understanding the ways that biology and culture intertwine in what is known as biocultural evolution, and the ways that behavior and culture can be in many respects “imprinted” or “embodied” in human skeletal and dental biology. There are actually a wide range of new methods, approaches, and even research designs spanning DNA analysis, paleoepidemiology, 3D imaging, and bioarchaeological theory I’ve been trying to develop over the last decade.

However, I think the stated goal of my project in Peru is really the most daunting: within the next 30 years, I would like to develop a basic biocultural reconstruction of the entire history of Peru’s Lambayeque Valley from its first inhabitants to its modern peoples. The current 15 yea r phase is focused on the last 2000 years of prehistory and the roughly 300 years of colonial occupation, and the work is progressing well. Because Lambayeque was a true center of independent civilization in the Andes and the Americas as a whole, understanding the course of civilization here can tell a broader story of the human history in the Americas.

r phase is focused on the last 2000 years of prehistory and the roughly 300 years of colonial occupation, and the work is progressing well. Because Lambayeque was a true center of independent civilization in the Andes and the Americas as a whole, understanding the course of civilization here can tell a broader story of the human history in the Americas.

5. Overall, how did your college education help prepare you for life and your career?

Plattsburgh was fundamental to preparing me for my life and career. I carry my experiences from Plattsburgh with me everywhere. There are practical things such as the skills involved in archaeological excavation that Gordon Pollard taught me or the nuts-and-bolts aspects of human skeletal biology and paleopathology that Mark Cohen imparted. But Plattsburgh’s deepest contributions are a bit more intangible.

The place itself was like a cradle of learning. Former honors program director David Mowry in particular made me conscious of the life of the mind, the value of curiosity, and never being satisfied with what you think you know – always explore and critically probe. He made me fall in love with rationality and logic. I also reflect to some degree the passion and intensity of my former professors — how they loved to share what they felt was important knowledge about humanity.

As a professor myself now, I try to emulate them. I do my best to follow the model of the “teacher-scholar” with my own students. I remember on the first day of classes—Fall 1996—my calculus professor Bob Hofer gave the students a 3×5 note card. It was a good bookmarker, but it was stamped with two words: “Don’t Quit.” The note card, sadly, I think is long gone. But the message and the meaning of those two words I still carry with me.

6. What advice do you have to share with SUNY students?

I fear that some of my advice might sound clichéd, but a few things I have found to be true: pursue in life what you love, and do what you enjoy. Also, I have discovered through more hard work, blood, sweat, and tears than I would like to admit, that doing the hard things in life often represents the best things we can do with ourselves; there’s something to be said for tenacity and just plain stubbornness when it gets right down to it. Always challenge yourself, and never be truly satisfied with who you are at the moment. Your education provides you with a toolbox, filled with what gives you power as a person and a citizen: knowledge, critical thinking, and a role in shaping all our futures. Never feel you have no role or can have no impact—one thing I learned at Plattsburgh was that even little changes can eventually produce big results.

I fear that some of my advice might sound clichéd, but a few things I have found to be true: pursue in life what you love, and do what you enjoy. Also, I have discovered through more hard work, blood, sweat, and tears than I would like to admit, that doing the hard things in life often represents the best things we can do with ourselves; there’s something to be said for tenacity and just plain stubbornness when it gets right down to it. Always challenge yourself, and never be truly satisfied with who you are at the moment. Your education provides you with a toolbox, filled with what gives you power as a person and a citizen: knowledge, critical thinking, and a role in shaping all our futures. Never feel you have no role or can have no impact—one thing I learned at Plattsburgh was that even little changes can eventually produce big results.

For all that I have done, I have also failed a lot. Don’t be afraid of failing. Learn from your mistakes, and when you err, just try to make sure it’s an original mistake. Also, no matter what you do, cultivate the life of the mind within yourselves. Always question. Seek answers to your questions and to what is yet unknown. Explore. And what you’ll find is that the life of the mind is not some insular, cerebral state of being. It translates into your actions and deeds as you go forth and take the next steps in a fuller life.