The degenerative eye disease retinitis pigmentosa (R.P.) affects one in 3,000 people. The disease is caused by a gene mutation that damages rod photoreceptors, or light-sensing cells, in the eye. The symptoms of the disease may first appear in childhood, but the decreased loss of vision that occurs throughout the lives of those afflicted often leads to diminished night vision or tunnel vision.

A good analysis to explain the effects of RP is that of a television or computer screen. The pixels of light that form the image on the screen that we refer to as resolution, like 1080p resolution, can be compared to the millions of light receptors on the retina of the eye. The fewer pixels on a screen, the less distinct will be the images it will display, the difference between your old tube TV in the basement and that new flat screen. As a person’s RP gets worse and worse, fewer than 10 percent of the light receptors in the eye receive light, leaving sufferers to view the world in a limited way.

While there is no cure for retinitis pigmentosa yet, researchers at SUNY Upstate Medical University and SUNY Cortland have collaborated to gather new information that may help accelerate research on new treatments. In a study published by Cell Press in the Biophysical Journal earlier this year, researchers uncovered new information into what causes the outer segment of light-sensing cells to snap under pressure, which can cause blindness.

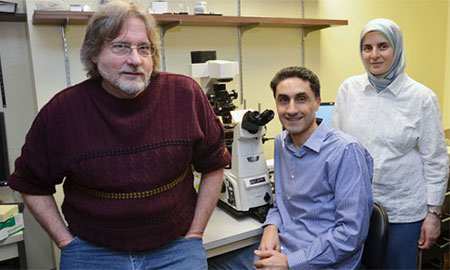

The trio of researchers participating in the study from Upstate are Barry Knox, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of Neuroscience and Physiology; Mohammad Haeri M.D., Ph.D., and Aphrodite Ahmadi, Ph.D., from SUNY Cortland.

Ahmadi, the senior study author, said the findings provide the first theory that explains how the structural rigidity of the outer segment can make it prone to damage. “Our theory represents a significant advance in our understanding of retinal degenerative diseases,” she said.

The outer segment of photoreceptors in the eyes consist of discs that are packed with a light-sensitive protein called rhodopsin. Mutations like RP that affect these photoreceptors often destabilize the outer segment and damage its discs. But until now, it was unclear which structural properties of the outer segment determine its susceptibility to damage.

To address this question, the SUNY researchers examined frog tadpole photoreceptors under the microscope while subjecting them to fluid forces. They found that high-density bands packed with a high concentration of rhodopsin were very rigid, which made them more susceptible to breakage than low-density bands consisting of less rhodopsin. Their model confirmed their experimental results and revealed factors that determine the critical force needed to break the outer segment. The findings support the idea that mutations causing rhodopsin to aggregate can destabilize the outer segment, eventually causing blindness.

Measuring the fragility of these photoreceptors is helpful, said Haeri. “If this is the reason for some blindness, we can come up with a treatment to increase their flexibility and prevent these rods from bending or breaking, which ultimately may save sight for individuals.”

Haeri says the next step may be to screen different drug candidates in mice to see if the photoreceptor rods can become more stable.

Knox says collaborative research, such as that done with SUNY Cortland, can accelerate such activity by tapping into the expertise available at other campus. Knox’s work at SUNY Upstate is also part of the University’s Center for Vision Research, which collaborates not only with SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, but public and private colleges around the world, too.

“We can collaborate with researchers in different time zones or we can collaborate with experts just down Interstate 81,” Knox said, referring to work done at SUNY Cortland in this most recent study. “In this case, the collaboration brought together a physician-trained scientist, a physicist and a molecular biologist to advance our understanding of the causes of blindness.”

Learn more at News from Upstate Medical University.