Nearsightedness—or myopia— comes from the Greek myops, literally meaning “closing the eyes.” Myopic also has a metaphorical usage in English that connotes shortsightedness or lacking understanding—a definition that may describe the prevailing treatment of myopia. Fortunately, thanks to funding from the SUNY Brain Network of Excellence, a multidisciplinary team of SUNY researchers is working to help open our eyes to a new understanding of what drives myopia onset and progression, with a goal of uncovering new treatments for this widespread eye disease.

The SUNY team working on this research is led by Dr. Stewart Bloomfield, Associate Dean for Graduate Studies and Research at SUNY College of Optometry. He is joined by Eduardo Solessio, Ph.D., assistant professor of ophthalmology and neuroscience and physiology at SUNY Upstate Medical University; Drs. Jose Manuel Alonso and David Troilo from SUNY College of Optometry; and Dr. Gary Matthews, professor of neurobiology and behavior at Stony Brook University.

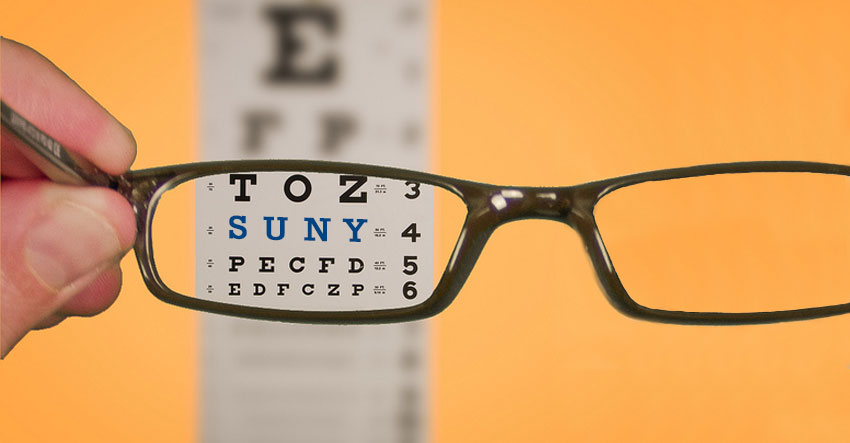

Myopia is a highly pervasive medical condition, affecting 42 percent of adults in the U.S. and more than 80 percent of young adults in Asia. It’s also a disease that’s on the rise. Currently, 1.4 billion people globally suffer from myopia, and that number is projected to rise to 2.4 billion by 2050. Yet to date it has been managed only symptomatically with prescription glasses, contact lenses, or laser surgery, which do not prevent myopia’s progression over time.

Numerous studies suggest that the increased incidence of myopia may be due in part to lower exposure to natural light, a theory that is supported by higher myopia rates in North America and Asia than in South America and Africa, where people spend much more time outdoors on average. “We know that our eyes weren’t created to be indoors all the time,” says Dr. Stewart Bloomfield. “When we spend too much time indoors, we don’t get enough of the kind of light our eyes need.”

Dr. Bloomfield cautions that myopia should not be viewed a harmless nuisance, but rather as a serious condition—because it increases a person’s risk of vision-threatening eye diseases like glaucoma and cataracts. Given myopia’s huge impact and potential implications, it may seem surprising that more effort hasn’t been put into better understanding myopia’s causes and potential treatments.

Focusing our research

Dr. Bloomfield says that myopia has not been adequately studied, but that the funding from SUNY Brain could lead to important advances that could benefit billions of people around the world. “This is a very important health problem, and with this research, we’ll have much more information about myopia’s causes and ultimately help us offer actual treatments.”

To study both what brings myopia on and what makes it worse, the SUNY team will be looking at multiple environmental and genetic risk factors for myopia, developing innovative animal models using zebrafish and mice. These species lend themselves to quick genetic changes, allowing for accelerated findings.

Depending on the results of the study, Dr. Bloomfield says, the team might work on a wearable electronic device that would help track “illuminance”, or a person’s exposure to the kind of light necessary for healthy eye development. If they are able to isolate the genetic marker responsible for myopia, the study may even lead to research on gene therapy. While myopia may have multiple genetic causes, the team believes that a protein called Connexin 36 could be a prime suspect. With the help of lab mice that have Connexin 36 “knocked out”, the SUNY team hopes to learn a lot about how this protein may impact myopia. “We’re raising some mice in low light to compare how myopia develops in mice with and without Connexin 36,” Dr. Bloomfield explains. “Once we have completed this study, we’ll have a much better idea of the causes.” Then, he says, the team will be in a position to start work on wearable monitors and other kinds of treatments.

Asked whether this research will benefit adults who have more advanced myopia, Dr. Bloomfield says it’s too early to tell. But certainly the work of this team will shed new light on how nearsightedness might treated—or even prevented—in the future, perhaps stemming the tide of increasing cases of myopia worldwide.